Neo-humanism was introduced in 2023 as a cohesive framework for creating socially and environmentally sustainable economies where people can lead fulfilling lives (Sarracino and O’Connor, 2023). Its premise is that economic prosperity should serve as a means to improve well-being, rather than being an end goal in itself. Decades of research in this field provided valuable insights into what contributes to well-being, including the role of income growth. As a result, public policies have the unprecedented opportunity to prioritize directly people’s well-being, rather than solely focusing on economic growth in the hope that its benefits will eventually reach individuals. Urban centers can play a central role in initiating the Neo-humanist virtuous circle. Here are some practical guidelines and examples of successful urban reforms that promote social and environmental sustainability and can get the Neo-humanist virtuous cycle started.

There is overwhelming evidence that we are depleting the planet’s resources at an alarming rate. Global CO2 emissions have increased by more than 50% since 1990, reaching approximately 36.3 billion tons per year by 2021. This has contributed to a rise in global temperatures of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels[1], driving more frequent and severe climate events like heatwaves, floods, and wildfires.

The consumption of natural resources has been similarly unsustainable. Material extraction has quadrupled over the past five decades, with global resource use reaching 100 billion tons per year. Less than 9% of these materials are recycled, leading to severe environmental impacts. Compounding this, we are now venturing into deep-sea bed exploitation for minerals and rare earth elements. This practice has unknown ecological consequences. Besides the huge financial costs, mining the deep-sea bed threatens fragile ecosystems that have developed over millions of years, potentially destroying habitats before we even fully understand them. Scientists warn that deep-sea biodiversity may face significant risks due to habitat destruction, and the release of toxic substances into marine environments.

Meanwhile, biodiversity loss continues unabated. The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (2019) estimates that 1 million species are at risk of extinction in the coming decades. Moreover, soil degradation has affected over 33% of the world’s land area, reducing the productivity of agricultural lands and exacerbating food insecurity. Ocean acidification, caused by the absorption of about 30% of anthropogenic CO2, has led to a 26% increase in acidity since the industrial revolution, putting marine life, especially coral reefs, at serious risk. Coral reefs support roughly 25% of all marine species, and their loss would have profound effects on marine biodiversity and human communities that rely on them.

The Sustainable Development Goals Report published by the United Nations in 2024 confirms that worldwide, there has been little or no progress in the SDGs related to the environment[2].

The origins of unsustainability

Why is this happening? There are two prevalent explanations for the persistence of unsustainable behaviors. The first is that people value short-term comfort and convenience more than long-term environmental health. The underlying assumption here is that people are too much focused on personal gains to care about collective losses.

The second explanation is rooted in the idea that people do not know how much harm they cause to the planet. Advocates of this perspective argue that if individuals were more aware of the long-term effects of climate change, deforestation, biodiversity loss, and pollution, they would adopt environmentally-friendly behaviors. People might not realize, for example, that their daily actions – like driving cars, consuming fast fashion, or wasting food – contribute to larger systemic problems. Thus, the belief is that ignorance, rather than apathy, is the primary barrier to adopting more sustainable practices.

Either way, both explanations track the origins of unsustainability back to individuals, who are regarded as the ultimate responsible for consumption. The conclusion is that people must be guided, nudged or even coerced into adopting sustainable behaviors. Considering the current trajectory of environmental degradation, it is clear that all the efforts adopted to make our consumption patterns more sustainable approach have been ineffective so far. This failure likely stems from our limited understanding of the deeper factors driving people to engage in unsustainable behaviors. Rather than focusing solely on external incentives or punishments, sustainability would benefit from a deeper understanding of the psychological, and social influences that shape these behaviors. Without addressing the root causes, strategies to enforce sustainability are unlikely to succeed.

In fact, both explanations rest on a narrow and overly simplistic view of human nature – one that sees people as self-centered, materialistic individuals with insatiable needs. Such description matches well the textbook characterization of homo oeconomicus, but does not find empirical support in reality.

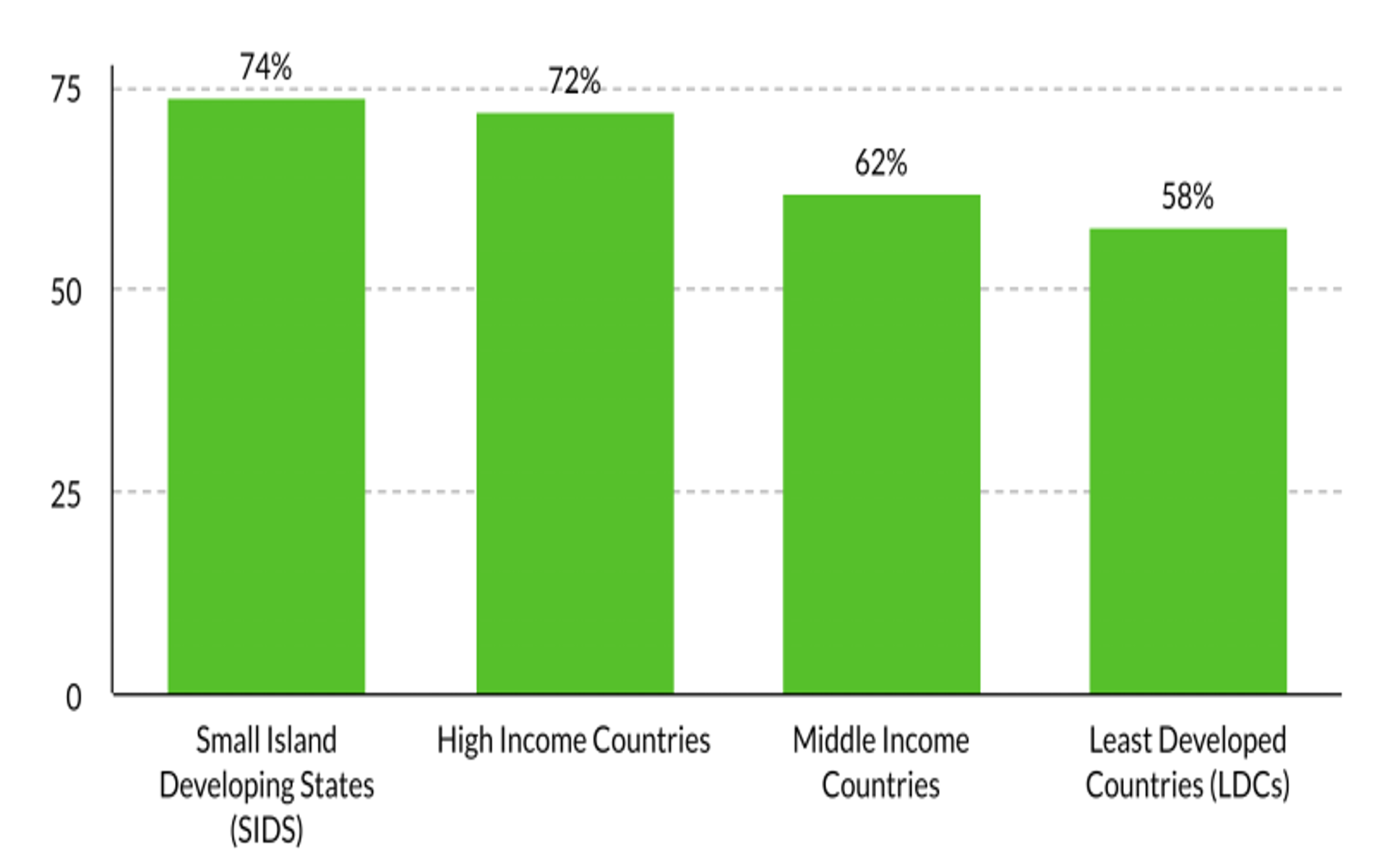

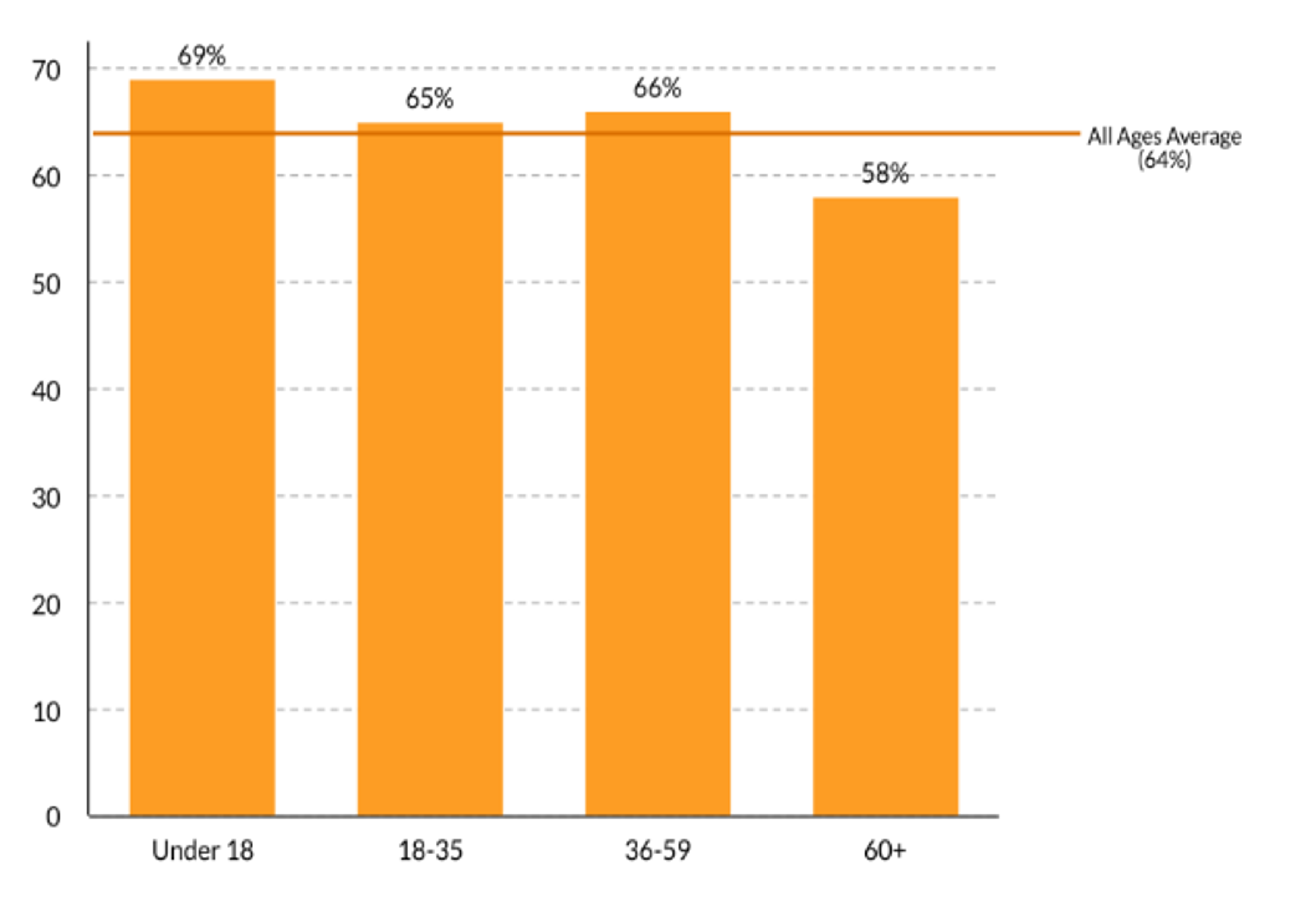

For instance, evidence suggests that people do care about the future and are concerned about the planet’s well-being. For instance, a global study by the UNDP in 2021 found that at least 60% of people worldwide, both elderly and young people – in developed and developing countries, believe there is a climate emergency (see figure 1). The Edelman Trust Barometer published in 2022 revealed that 75% of respondents worry about climate change, a concern second only to job security. In the European Union, climate change and environmental issues rank among the top concerns for citizens, according to the Eurobarometer (2019).

Figure 1. Public belief in the climate emergency, by country (Panel A) and age (Panel B) group

Panel A

Panel B

Source: UNDP, The People’s Climate Vote, Jan. 2021, https://www.undp.org/publications/peoples-climate-vote

Moreover, people’s concerns about the future significantly affect their well-being. An analysis of seven national and international datasets based on answers of several thousands of respondents from developed and developing countries revealed that individuals who anticipate a bleak future tend to experience lower levels of well-being than others. The effect size is comparable in magnitude to the negative impact of becoming unemployed (Bartolini & Sarracino, 2018). It is worth emphasizing that the analysis puts in relation various measures of subjective well-being with answers about how respondents see the distant future, one that concerns future generations and not the respondent directly. This demonstrates that on average people care for the planet’s future, and their sense of environmental and social instability profoundly affects their overall quality of life.

Social Unsustainability

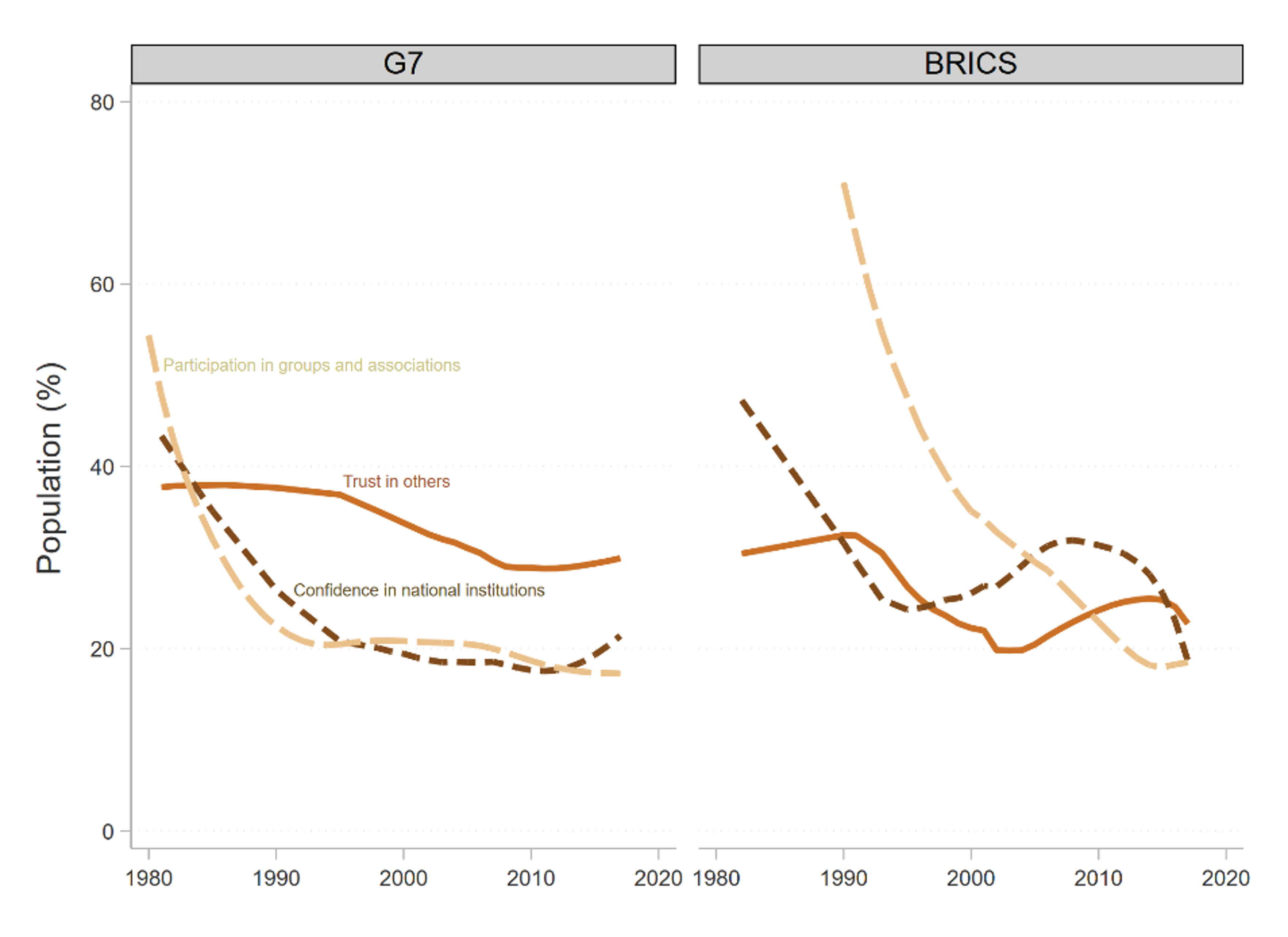

A less discussed but equally critical aspect is that modern societies are socially and not only environmentally unsustainable. Social cohesion is weakening, and people’s ability to cooperate towards common goals is diminishing in many modern countries. For example, global trust in institutions is at historically low levels, with Edelman’s Trust Barometer (2022) reporting that only 47% of people trust their governments. In the United States, for example, the General Social Survey (GSS) has tracked interpersonal trust since 1972, and the most recent data shows that only about 30% of Americans believe that “most people can be trusted,” compared to 46% in the 1970s. Similar trends are seen across Europe and many parts of the Global South.

This decline is not limited to developed economies (Sarracino and Mikucka, 2017); it is a global phenomenon, affecting both developed and developing countries alike (see Figure 2). On average, we observe declining trust in others, in institutions, and in participation in groups and association in both mature economies (see the left panel in Figure 2) and in developing countries (see the right panel in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in trust in others, in institutions and in membership, by groups of countries: the G7 members (left) and the BRICS (right)

Source: author’s own elaboraton of SDR 2.0 data.

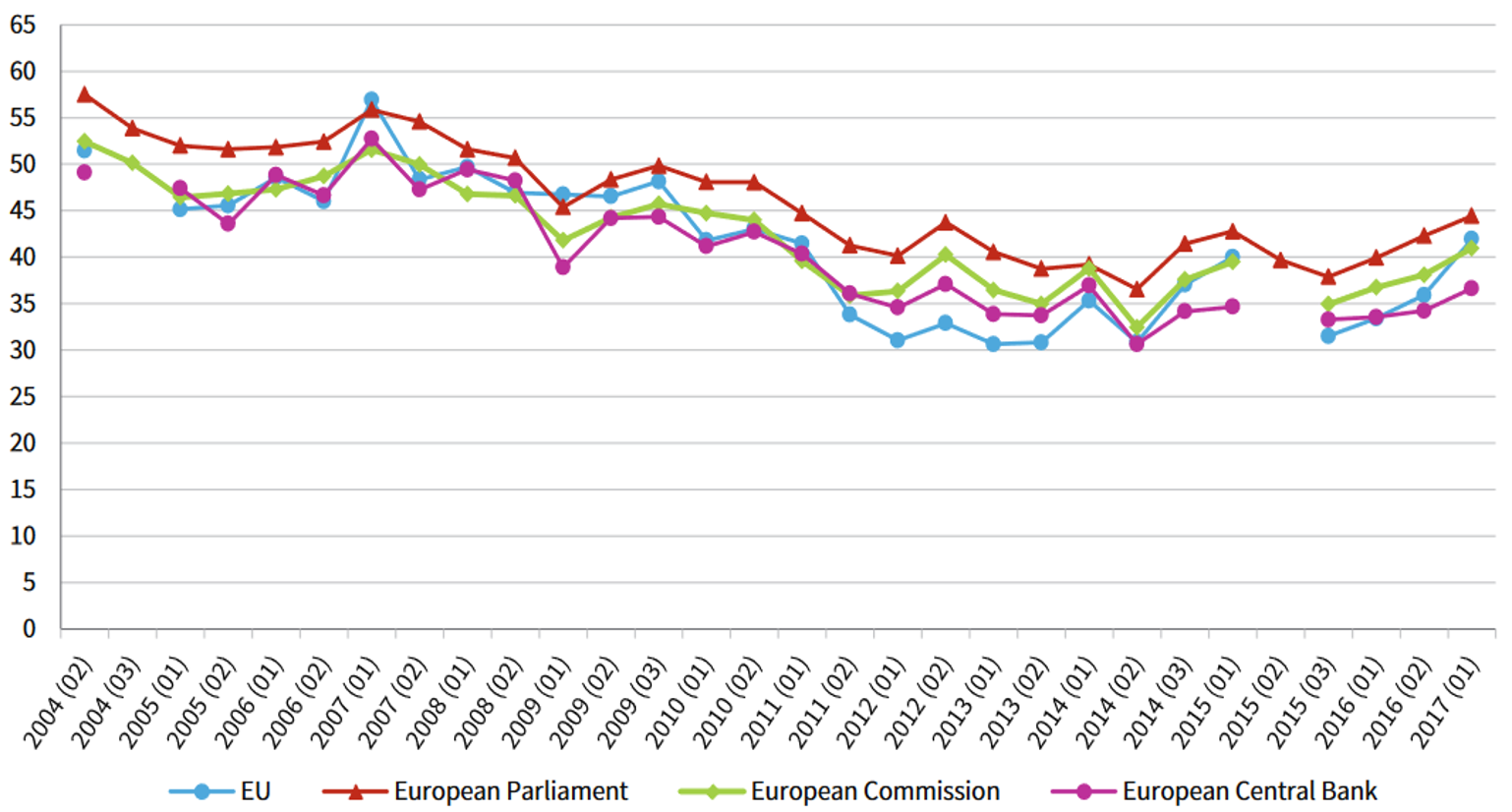

Figure 3 shows a long-term decline of trust in the main European institutions: the Parliament, the Commission, the Central Bank and the Union as a whole.

Figure 3. Trust in European Union institutions, EU 28, 2004-2017, population aged 15 and over (%)

Note: Eurobarometer data. The numbers after each year refer to the Eurobarometer edition. Source: Eurofound, 2018.

In other words, the breakdown of trust and, more in general, of social cohesion prevents collective action, including protecting the environment and pursuing sustainability. When trust in others and institutions declines, people become less willing to cooperate for the common good, focusing instead on personal or immediate concerns. As a result, collective action—essential for addressing global challenges like climate change—becomes increasingly difficult to mobilize. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a good example of this mechanism: countries where trust was higher introduced less stringent policies to contain the virus and recovered faster from the peak of infection than other countries, with overall less losses. Without trust, the willingness to invest in public goods such as clean air, biodiversity, or community health weakens, further entrenching unsustainable practices.

History offers other examples where trust and cooperation enabled successful collective action. For instance, extensive global vaccination efforts and surveillance allowed to eliminate smallpox by 1980. This result was possible thanks to substantial coordinating efforts among countries, who trusted the guidance of the World Health Organization (WHO), shared information, and pooled resources to lead a successful worldwide vaccination campaign[3]. Another example concerns the hole in the Earth’s ozone layer, one of the most feared environmental dangers for humanity until twenty years ago. In 2023, the World Meteorological Organization announced that the atmospheric layer that protects our planet from ultraviolet radiation is set to heal by 2040 over most of the world[4]. The ozone layer has been steadily improving thanks to Governments’ coordinated actions following the 1989 Montreal Protocol, an international agreement to eliminate ozone-depleting substances, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). The Protocol enabled a unified global response, countries recognized the mutual benefits of protecting the ozone layer and supported developing nations in their transition. These examples show that trust and cooperation are essential for the global community to effectively tackle major collective challenges.

The breakdown in the ability to cooperate to achieve common goals, thus, offers an alternative explanation of unsustainability to the two prevalent ones.

An alternative explanation of unsustainability

People may adopt unsustainable behaviors even if they care and are aware of environmental decay. Actually, the more they are anxious about the environment, the more they can adopt unsustainable behaviors. This paradoxical outcome is possible when cooperation to achieve common goals is impossible. For instance, when trust is scarce, individuals can not rely on others to do their part in a collective effort, such as protecting the environment. Hence, they will turn to private, individual solutions to protect themselves and their dear ones against a collective problem, such as environmental decay. The sum of all individual solutions worsens the initial problem, ultimately leading to unsustainability. A key point here is that when people are compelled to find personal solutions to collective problems, no amount of nudging or coercion can effectively change their behavior. People anxious about the future and determined to secure their own and their loved ones’ well-being will continue to pursue individual goals, often at the expense of the collective good. This explains why environmental initiatives have failed to yield significant results: the more people worry about the environment and feel left alone in addressing these challenges, the more likely they are to seek individual solutions. In essence, unsustainability results from a massive coordination failure. Instead of working together to preserve common goods—such as a healthy environment or strong social bonds—individuals prioritize their own security. Unsustainability, then, is not simply a result of ignorance or apathy, but of individual efforts to shield themselves from the erosion of public goods.

In sum, 1. the impossibility of collective action to address collective problems stimulates private consumption and environmental degradation; 2. the economy grows because of people’s private efforts to cope with collective problems; 3. anxiety about the environment, and the future in general, pushes people to adopt unsustainable behaviors. These are three elements of a self-reinforcing vicious cycle that creates formidable consumers; probably all unhappy, unhealthy, overworked, lonely, stressed, and all obsessed by money and consumption. This vicious cycle creates societies where money becomes central in people’s lives, because what they can or cannot do depends increasingly on how much money they control. From this point of view the growth of the economy is not a sign of progress.

Neo-humanism: a change is possible

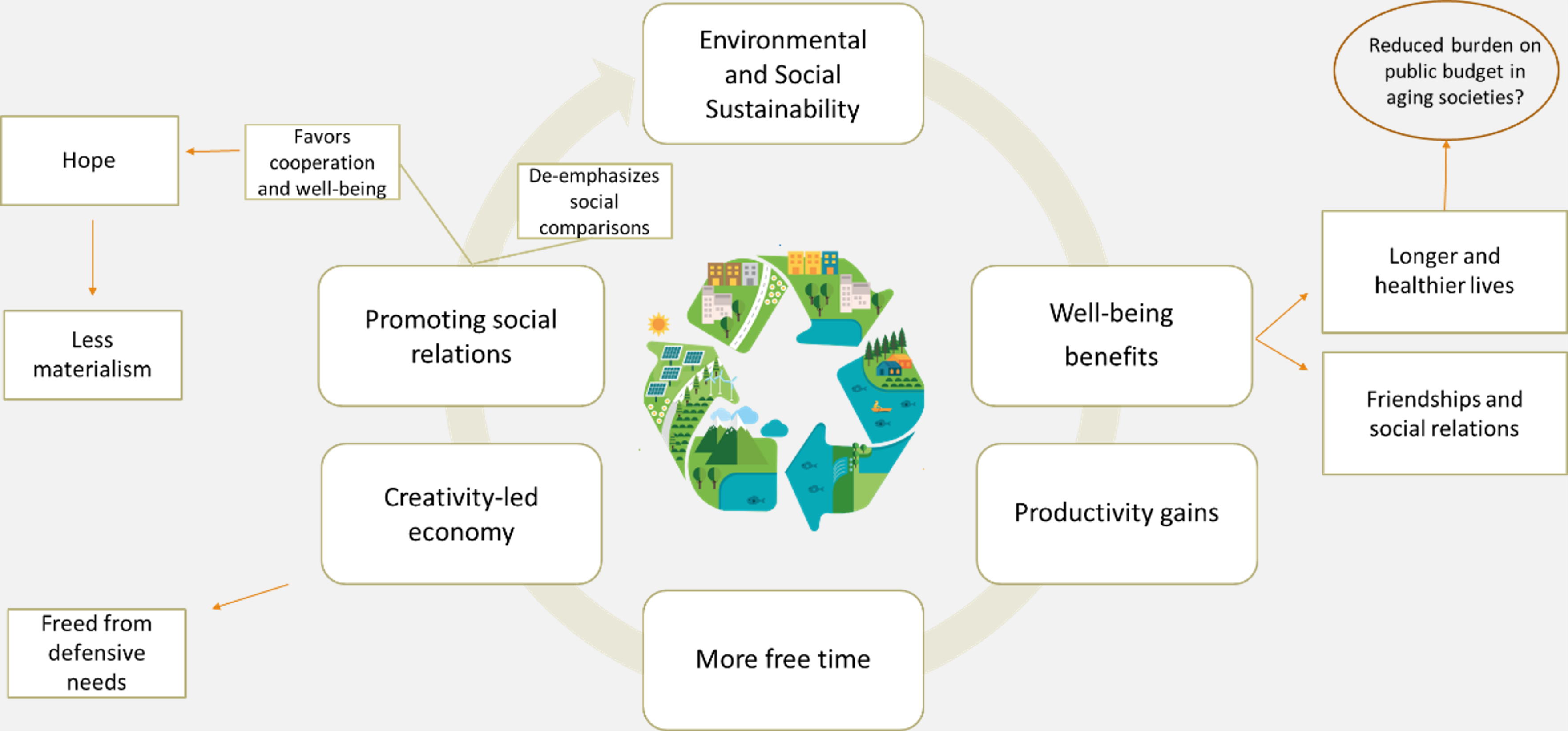

Neo-humanism indicates a path to socially and environmentally sustainable societies by prioritizing well-being in decision making. The idea is that we can adopt policies to improve well-being directly, rather than focusing our policy efforts to ensure economic growth – with the hope that it will eventually benefit well-being. Thanks to decades of research on the causes and consequences of well-being, we know a lot about the key elements that contribute to well-being, such as strong social connections, good health, meaningful employment, ample free time, and access to green, walkable spaces. Promoting these factors will help decoupling well-being from consumption. In the remaining of this section, I will briefly illustrate the main features of the neo-humanist virtuous cycle (see Figure 4 for a diagram illustrating the main steps of the cycle).

For instance, fostering social relationships significantly enhances well-being, and, as advertising experts know well, happier people tend to consume less than others. This is partly because individuals with strong social ties and trust in their communities are less likely to engage in conspicuous consumption as a means of coping with dissatisfaction or isolation. Moreover, when trust in others and institutions is high, people are more inclined to cooperate on shared goals, such as environmental protection, which is essential for sustainability.

Additionally, social comparison – a key driver of conspicuous consumption – plays a negligible role for the well-being of individuals with rich social lives. This suggests that strengthening social bonds reduces one of the engines of unsustainable consumption, and contributes to socially and environmentally sustainable societies. This makes for more satisfying lives.

Figure 4. The neo-humanist virtuous cycle

Source: Sarracino & O’Connor, 2023.

Research indicates that engaging in eco-friendly and pro-social behaviors significantly enhances subjective well-being (Zawadki et al., 2020; Helliwell et al., 2017). Greater well-being, on the other hand, yields broader societal benefits. For instance, happier people tend to live longer, healthier lives, which in turn could contribute to the sustainability of public budgets in aging societies by reducing healthcare costs and extending healthy life expectancy.

Well-being is also associated with efficiency gains, as happier people tend to be less absent, more cooperative, and to change job less frequently. The empirical evidence supporting this relation is extensive. Research by DiMaria and colleagues (2020) shows that increasing life satisfaction by one point[5] in countries such as Germany or France could lead to efficiency gains that are equivalent to nearly 80 working hours. That is to say that improving well-being by one unit would allow people to work nearly two weeks less per year while leaving the output level unchanged. Similar research by Peroni and colleagues (2022) indicates that well-being growth leads to nearly 5% gross value added growth across industries in Europe. In other words, promoting well-being leads to efficiency gains that can be used to reduce working time, favor work-life balance, or finance policies to promote social relations. Efficiency gains open up possibilities to enhance quality of life, all while maintaining the level of economic output unchanged. This means that we could finally decouple well-being from production (and consumption), meaning that individual well-being would not be directly tied to consumption or material wealth. In other words, people would be able to lead satisfactory lives in a socially and environmentally compatible economy; an economy that is not driven by defensive needs, but by creativity. How can we promote social relations?

Cities as Engines of Change

There are many intervention areas to promote social relations and kick-start the neo-humanist virtuous cycle: in the workplace, through initiatives like mentorship programs or collaborative projects that encourage teamwork and communication; in schools, where group projects, peer mentoring, and extracurricular activities foster cooperation among students; in community-based farming or conservation projects, where people work together toward common environmental goals; through volunteerism, where individuals come together to serve a common cause, such as disaster relief, food drives, or animal rescue initiatives. Cities are part of the solution too.

Urban centers are places where people gather to organize their lives together, not merely spaces for production and consumption. This makes cities central to both the challenges and solutions of sustainability. The literature on urban planning is ripe with studies of how the built environment affects people’s ability to interact with each other, develop social relations, and lead satisfactory and healthy lives.

For instance, walkable, green spaces, comprehensive transportation networks, and co-designed public spaces can help promote trust, cooperation, and social cohesion – essential elements for creating sustainable societies. These features enable people to meet and interact in their daily routines, fostering a sense of community and shared responsibility.

Various studies found that people are more likely to engage in spontaneous conversations and build relationships in well-designed, walkable spaces. Even simple activities, such as dog walking, have been shown to strengthen social connections, when the urban environment supports such interactions (Graham & Glover, 2013; Koohsari et al. 2021) – but suitable spaces are necessary.

On the contrary, many modern cities are dominated by urban sprawl – disconnected streets, scattered housing, heavy reliance on vehicles, segregated land use, and limited residential mobility – and are poorly suited to foster social interactions. This kind of urban layout exacerbates social inequalities, particularly affecting the most vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, children, and individuals with disabilities. These groups often experience a loss of autonomy, as their ability to socialize depends heavily on the availability and time of others. This dependency further adds to collective stress and heightens the pressures related to time management, making daily life more challenging.

Modern cities can become incubators of social relations, well-being, and sustainability. Through deliberate planning, urban environments can foster stronger social connections, reduce inequalities, and create more inclusive, sustainable communities.

Promoting social relations within urban environments can be achieved through various key intervention areas that foster connection, trust, and cooperation among community members. Public spaces, such as well-designed parks, green areas, and community centers, provide opportunities for informal social interaction and recreational activities, enhancing mental health and community bonds. Walkability and transportation infrastructure, including pedestrian-friendly streets and bike lanes, facilitate spontaneous social exchanges and reduce car dependency, allowing people to interact more frequently. Shared living spaces and integrated residential and commercial areas, such as co-housing communities and mixed-use developments, encourage cooperation and daily social interaction. Cultural and recreational initiatives, like festivals, sports leagues, and community events, also play a vital role in bringing diverse groups together, fostering social cohesion and teamwork. Additionally, urban gardening and green initiatives provide a platform for collective environmental stewardship while strengthening social ties. Finally, participatory urban planning, where residents are actively involved in designing public spaces, promotes a sense of ownership and belonging, further enhancing social relations. By focusing on these areas, urban planners can create environments that nurture stronger social connections, build trust, and contribute to more resilient and sustainable communities.

Here are some guiding principles of urban initiatives to start a neo-humanist virtuous cycle:

- Developing multi-use green spaces to integrate nature into daily life: these spaces facilitate social relationships by offering inclusive environments that address the diverse needs and preferences of the community;

- Implementing comprehensive active transportation networks to decouple well-being from car-dependent lifestyles, while reducing environmental impact and promoting physical health through walking and cycling;

- Co-designing public spaces and amenities to foster a sense of belonging and satisfaction with urban environments. When residents have a say in the design of their shared spaces, they are more likely to take ownership and feel connected to their surroundings.

Creating something as simple as free, accessible, and safe public spaces where people can gather has a profound impact on social relations. These areas cultivate a sense of community and offer opportunities for interactions that improve overall well-being. These principles have been long recognized in urban design and have been successfully implemented in various cities worldwide, contributing to more socially cohesive and sustainable urban environments.

Social Urbanism

Social urbanism is an approach to urban design that integrates urban development with social policies, aiming to create more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable communities. This model has been successfully applied in several Latin American countries. The examples of Medellín, Colombia, or Favela Bairro in Rio de Janeiro are well-known. These projects focus on transforming marginalized neighborhoods by providing infrastructure improvements, public spaces, and essential services, while also fostering social inclusion. The approach has also gained recognition in Europe, with Barcelona’s superblocks serving as a prominent example. Barcelona’s initiative reorganizes urban spaces to prioritize pedestrians, limit vehicular traffic, and create healthier, more connected communities.

The core principles of social urbanism include inclusive urban design, ensuring that public spaces, parks, and transportation systems are accessible to all, especially to marginalized groups. Another key element is community participation, coupled with access to social services, ensuring that basic needs such as education, healthcare, and housing are met. Lastly, sustainability is central to this model, promoting equitable access to green spaces and environmentally conscious urban planning to enhance social well-being.

Anecdotal and qualitative evidence indicate that social urbanism initiatives improve social cohesion, reduce criminality, and enhance the overall well-being of local communities. However, the full impact of such projects, particularly in the Global South, is difficult to assess because of data limitations. An example from London provides an idea of the potential of such interventions.

The Low Traffic Neighborhoods of Waltham Forest

Since 2015, Waltham Forest, one of London’s Borough located in the North of the city, has been implementing Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) – a type of area-based intervention that removes through-traffic from residential streets. These measures free up streets for pedestrians and cyclists, improving the overall livability of neighborhoods.

A study published in 2021 demonstrated the significant effects of LTNs on reducing street crime, both within the LTNs and in surrounding areas (Goodman & Aldred, 2021). Compared to areas without interventions, LTNs were associated with a 10% reduction in recorded crimes. The most significant declines were observed in crimes such as violence and sexual offenses, public order disturbances, possession of weapons, criminal damage and arson, burglary, and vehicle-related crimes.

The study further revealed that the longer an LTN had been in place, the greater the reduction in crime, with an 18% decrease in street crime recorded after three years of implementation. This suggests that LTNs have a cumulative positive effect over time. Additionally, a longitudinal study from 2016 to 2019 reported a 21% increase in walking among residents in Waltham Forest LTNs compared to the rest of Outer London, indicating a shift towards healthier and more sustainable modes of transportation (Aldred and Goodman, 2020). The effect size indicates that the average walking duration increased by nearly 12 minutes, extending the typical walk from one hour to approximately one hour and twelve minutes..

Importantly, the 2021 study found no evidence of increasing crime in adjacent areas. This indicates that LTNs did not move criminality elsewhere; they led to safer, more liveable neighborhoods overall. Following the success in Waltham Forest, LTNs were widely implemented across the UK in 2020, demonstrating their potential to create safer, healthier urban environments with reduced traffic and crime.

Conclusion

In summary, Neo-humanism presents a comprehensive framework for urban planning and policy that aims to create resilient, sustainable, and thriving cities, rooted in equity and collective responsibility. In practice, this approach advocates for people-centered urban design that prioritizes inclusivity, social justice, and ecological balance over economic needs. Cities should be organized in ways that reduce inequality by providing affordable housing, quality healthcare, and accessible public transportation. At the same time, promoting green infrastructure and strengthening community bonds are key to fostering healthier, more integrated and socially cohesive urban environments.

One of the central tenets of Neo-humanism is recognizing that relying on private solutions to solve public problems is a major source of unsustainability. Individual solutions often exacerbate inequalities and fail to address systemic issues such as waste management, transportation, and housing. To counter this, a collective, policy-driven approach is needed – one that addresses these challenges in a holistic manner and ensures that the benefits are shared equitably.

Furthermore, Neo-humanism shifts the focus from markets to people, emphasizing the importance of the quality of economic growth. Economic growth can benefit everybody or only a few; it can contribute to healthy communities or weaken the bonds between people. This is why in some countries the economy grows along with well-being, but not in others. By prioritizing well-being, neo-humanism offers a road-map for creativity-led economies that are socially and environmentally sustainable. This is great news for the prospects of sustainability. It means that people do not need to be coerced into adopting sustainable behaviors – a task that so far failed miserably; instead, they should be empowered to act pro-socially and pro-environmentally by placing well-being at the core of decision-making.

While specific strategies may differ between regions, the guiding principles of Neo-humanism – centered on equity, shared responsibility, sustainability, and cooperation – are relevant across both the Global North and South.

References

Aldred, Rachel, and Anna Goodman. 2020. “Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, Car Use, and Active Travel: Evidence from the People and Places Survey of Outer London Active Travel Interventions.” Findings, September

Bartolini, S., & Sarracino, F. (2018). Do people care about future generations? Derived preferences from happiness data. Ecological Economics, 143, 253-275.

DiMaria, C. H., Peroni, C., & Sarracino, F. (2020). Happiness matters: Productivity gains from subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(1), 139-160.

Eurofound (2018), Societal change and trust in institutions, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Goodman, A. and Aldred, R. (2021). The impact of introducing a low traffic neighbourhood on street crime, in waltham forest, london. Findings.

Graham, T. M., & Glover, T. D. (2014). On the fence: Dog parks in the (un) leashing of community and social capital. Leisure Sciences, 36(3), 217-234.

Helliwell, J. F., Aknin, L. B., Shiplett, H., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2017). Social capital and prosocial behaviour as sources of well-being (available here: https://www.nber.org/papers/w23761).

Koohsari, M. J., Yasunaga, A., Shibata, A., Ishii, K., Miyawaki, R., Araki, K., … & Oka, K. (2021). Dog ownership, dog walking, and social capital. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1-6.

Peroni, C., Pettinger, M., & Sarracino, F. (2022). Productivity Gains from Worker Well-Being in Europe. International Productivity Monitor, (43), 41-61.

Sarracino, F., & Mikucka, M. (2017). Social capital in Europe from 1990 to 2012: Trends and convergence. Social Indicators Research, 131(1), 407-432.

Sarracino, F., & O’Connor, K. J. (2023). Neo-humanism and COVID-19: Opportunities for a socially and environmentally sustainable world. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 18(1), 9-41.

Zawadzki, S. J., Steg, L., & Bouman, T. (2020). Meta-analytic evidence for a robust and positive association between individuals’ pro-environmental behaviors and their subjective wellbeing. Environmental Research Letters, 15(12), 123007.