The climate crisis is intensifying dramatically. The 1.5-degree target is moving further and further out of reach. At the same time, the wealth of a small number of people is growing faster than ever. The Climate Inequality Report 2025 shows that these two developments are more closely linked than is often assumed. It is not only consumption, but above all ownership that determines who drives the climate crisis, who suffers from it, and who has the means to fight it. A just climate policy must therefore place questions of ownership at the center of its design.

Extreme wealth concentration and its climate impacts

The link between income and emissions is often discussed. Indeed, the segments of the global population with the highest income are responsible for a large share of global consumption-based emissions, while they themselves suffer comparatively little from the consequences of climate change. But wealth is at least as important as income. Those who own companies, real estate, or financial assets decide how production takes place, which technologies are used, and whether climate-damaging business models continue to exist.

Wealth is extremely unevenly distributed. According to the World Inequality Report 2026, the richest 10 percent of the world’s population own 75 percent of global wealth, while the poorer half owns almost nothing. This concentration means power, economic and political, including in climate policy. In addition, investment decisions in energy, industry, and infrastructure are increasingly in private hands, while many states have little wealth left to carry out the necessary investments themselves.

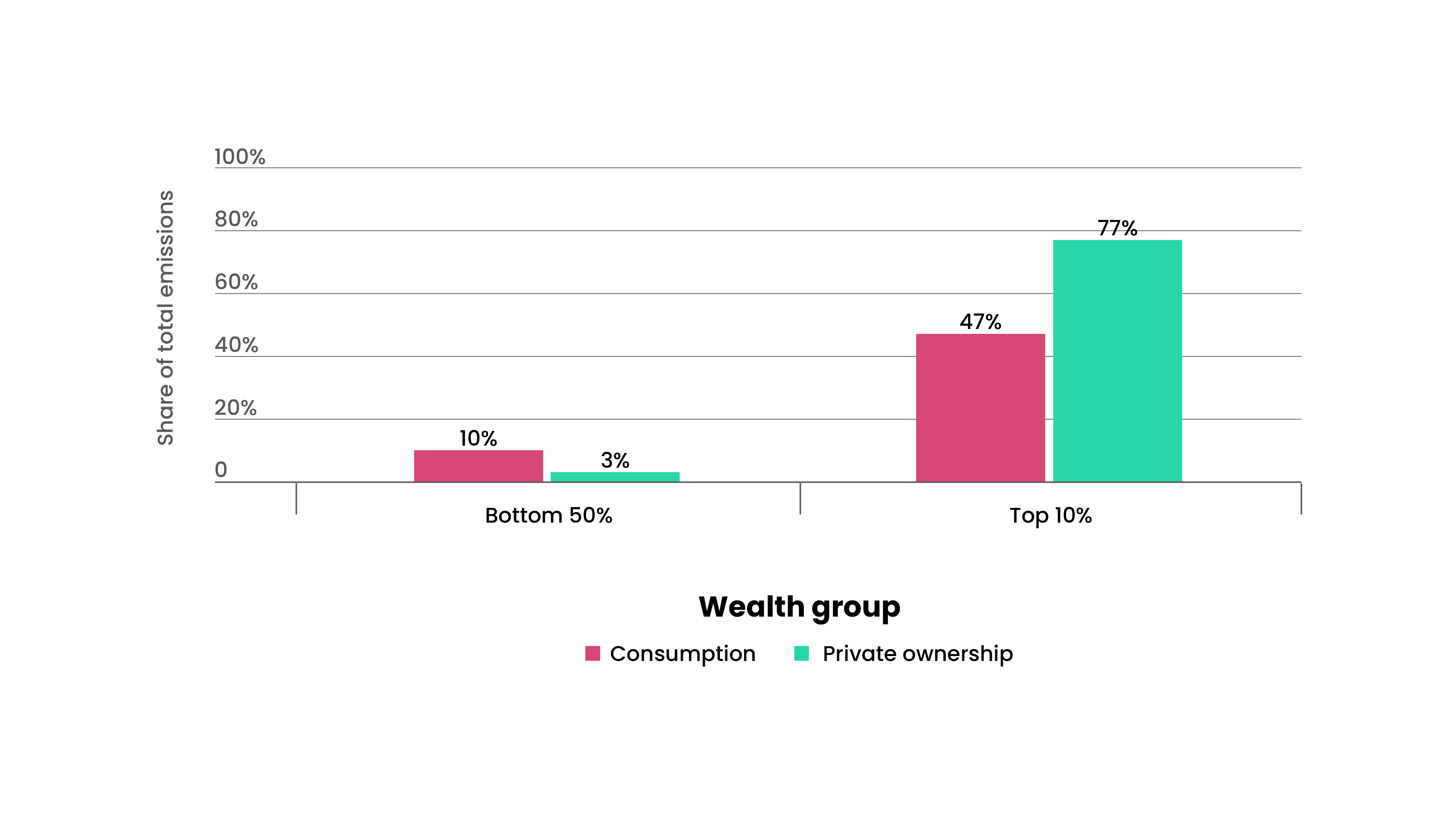

This concentration of wealth has concrete consequences for the climate. When emissions are attributed to the owners of the companies that directly cause them, the contribution of the poorer half of the world’s population falls from 10 to 3 percent compared to the consumption-based approach; by contrast, the share of the richest 10 percent in global emissions rises from 47 to 77 percent (Figure 1).

The continued profitability of climate-damaging investments is also evident in the enormous sums that still flow into new oil, gas, and coal projects, even though it has long been clear that their use alone would make climate targets unattainable. As the Climate Inequality Report 2025 shows, many of these projects are located in the Global South but are controlled by investors from the Global North. As a result, wealthy individuals continue to benefit from climate-damaging production, while other regions often bear the ecological and social costs.

Shares of global total emissions

Source: Chancel, L. et al. (2025) Climate Inequality Report 2025

The climate transition as a future redistribution issue

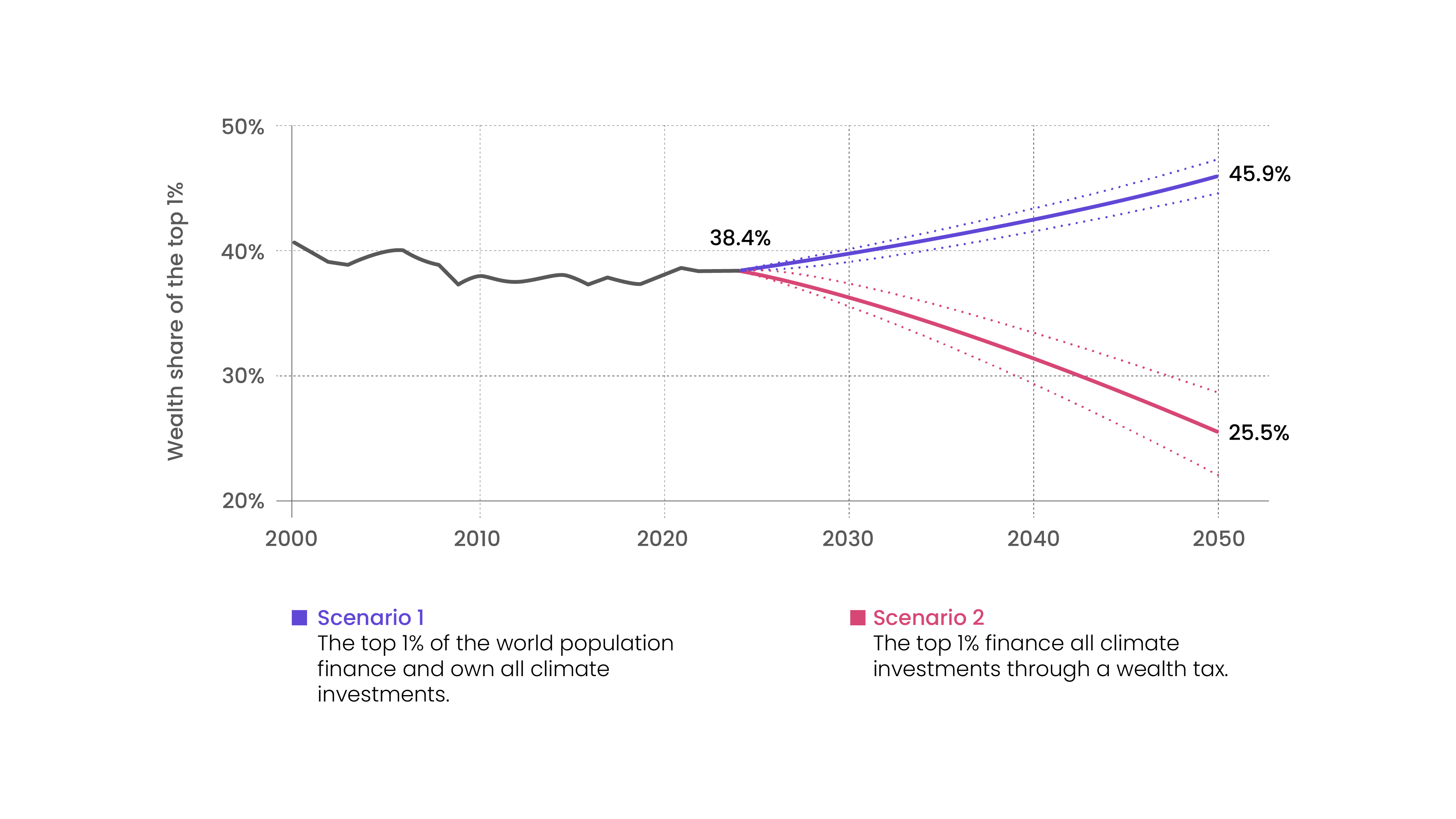

At the same time, the climate transition offers a unique opportunity for wealth redistribution. If fossil fuels are consistently phased out, climate-damaging assets will lose significant value. At the same time, the transformation to a climate-neutral economy requires massive investments in new infrastructure: according to the Climate Policy Initiative, around 266 trillion US dollars will need to be invested in low-emission infrastructure over the coming decades. This corresponds roughly to the value of the entire global capital stock in 2022. Those who make these new investments will shape the future distribution of wealth. Figure 2 shows projections of the required climate investments up to 2050 combined with today’s wealth distribution: if the richest 1 percent of the world’s population finance and control the new investments, their share of wealth could rise from the current 38.4 percent to nearly 46 percent by 2050 (Scenario 1). If, by contrast, the climate transition is financed through a wealth tax and the newly created wealth is subsequently redistributed downward, this share could decline significantly (Scenario 2).

Potential evolution of the wealth share of the richest one percent

Source: Chancel, L. et al. (2025) Climate Inequality Report 2025

A just climate policy must regulate ownership

A just climate policy must therefore not be limited to individual behavior. It must place questions of ownership at its core: for example, a ban on fossil fuel investments, as demanded by initiatives such as the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, could immediately make a substantial contribution to slowing the climate crisis. In addition, a wealth-based component could make carbon pricing far more progressive than a purely consumption-based tax, while generating public revenues that can be used specifically for low-emission investments. More broadly, the public sector should take an active role in financing and democratically controlling the expansion of climate-neutral infrastructure in order to advance the climate transition while simultaneously reducing existing wealth inequalities.

This article was first published in a longer version on the A&W blog

Photo by Arvind Vallabh on Unsplash