The rise of economic insecurity has become a major concern in recent years, influencing individual behaviours and outcomes. Economic insecurity is broadly understood as uncertainty about future economic stability. In our article “Economic insecurity and political preferences” published in Oxford Economic Papers in 2023, we ask whether economic insecurity affects the way in which people vote. Economic insecurity is proposed here as an additional explanation of populist preferences to the cultural backlash against progressive values, such as cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism or status threat.

Economic Insecurity and Political Preferences

Despite its critical role in shaping economic, political, and social outcomes, economic insecurity remains a concept without a universally-accepted definition. Prior research has addressed this insecurity in a variety of ways, such as changes in the unemployment rate, falls in per capita income, or shifts in subjective perceptions of financial stability. Given the complexity of fully taking into account all of these dimensions, we propose a simplified individual-level measure of economic insecurity.

Our approach defines economic insecurity axiomatically, capturing changes in individual economic resources – such as income – over time. From a theoretical point of view, our index of economic insecurity aims to measure the confidence with which individuals can face any potential future economic changes. This confidence is argued to depend on their past experiences of gains and losses in resources. From a technical point of view, our measure is constructed using a geometrically-discounted sum of income fluctuations, adhering to a set of standard axioms. Two key properties define this measure:

- Loss-monotonicity: a loss in economic resources from one period to the next increases insecurity, while a gain reduces it.

- Proximity-monotonicity: more recent fluctuations have a greater influence on insecurity.

Our insecurity measure requires data on the changes in economic resources of the same individual over a number of years. This can be done using data from two well-established long-term panel surveys: the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS – from 1995 to 2007) for the UK and the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP – from 1989 to 2018) for Germany. In both datasets, we consider annual household equivalent income (which is household income adjusted for the number of people who live in the household, reflecting the economies of scale from multiple people living together) as the main indicator of economic resources. The changes in annual household equivalent income over the past five years are then used to construct the measure of economic insecurity.

But does individual economic insecurity influence political preferences? Since insecurity is linked to both unemployment and income, we control for these factors, along with other demographic and socioeconomic variables such as wealth (proxied with homeownership), in a regression analysis. This allows us to isolate the effect of insecurity by comparing individuals with similar characteristics – such as sex, age, education, marital status, and labor-force status – who differ only in their economic insecurity levels. Our findings suggest that economic insecurity increases political engagement. Rather than discouraging participation, it appears to mobilize individuals, making them more likely to express support for a political party. The question is then: Which political groups benefit from this higher participation?

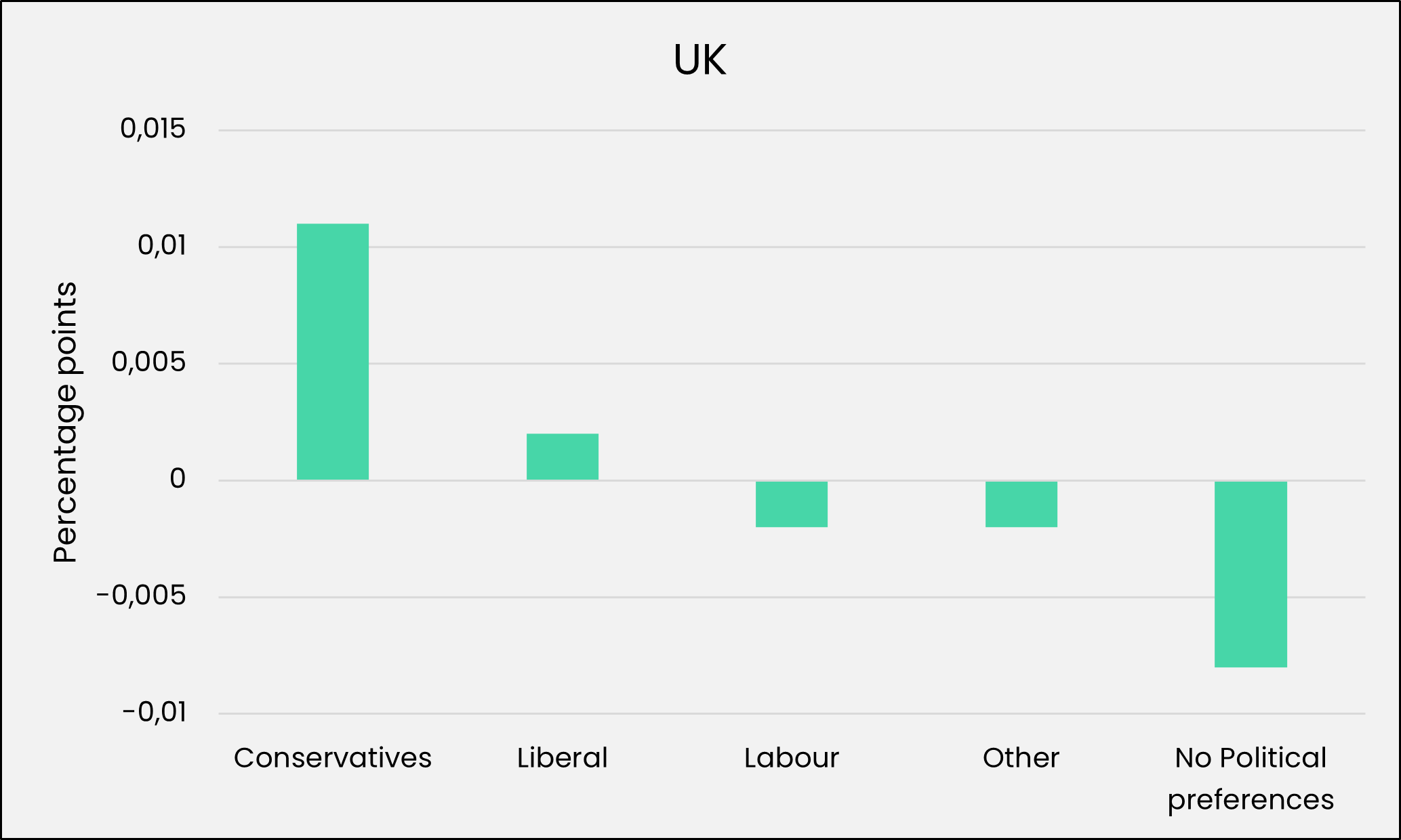

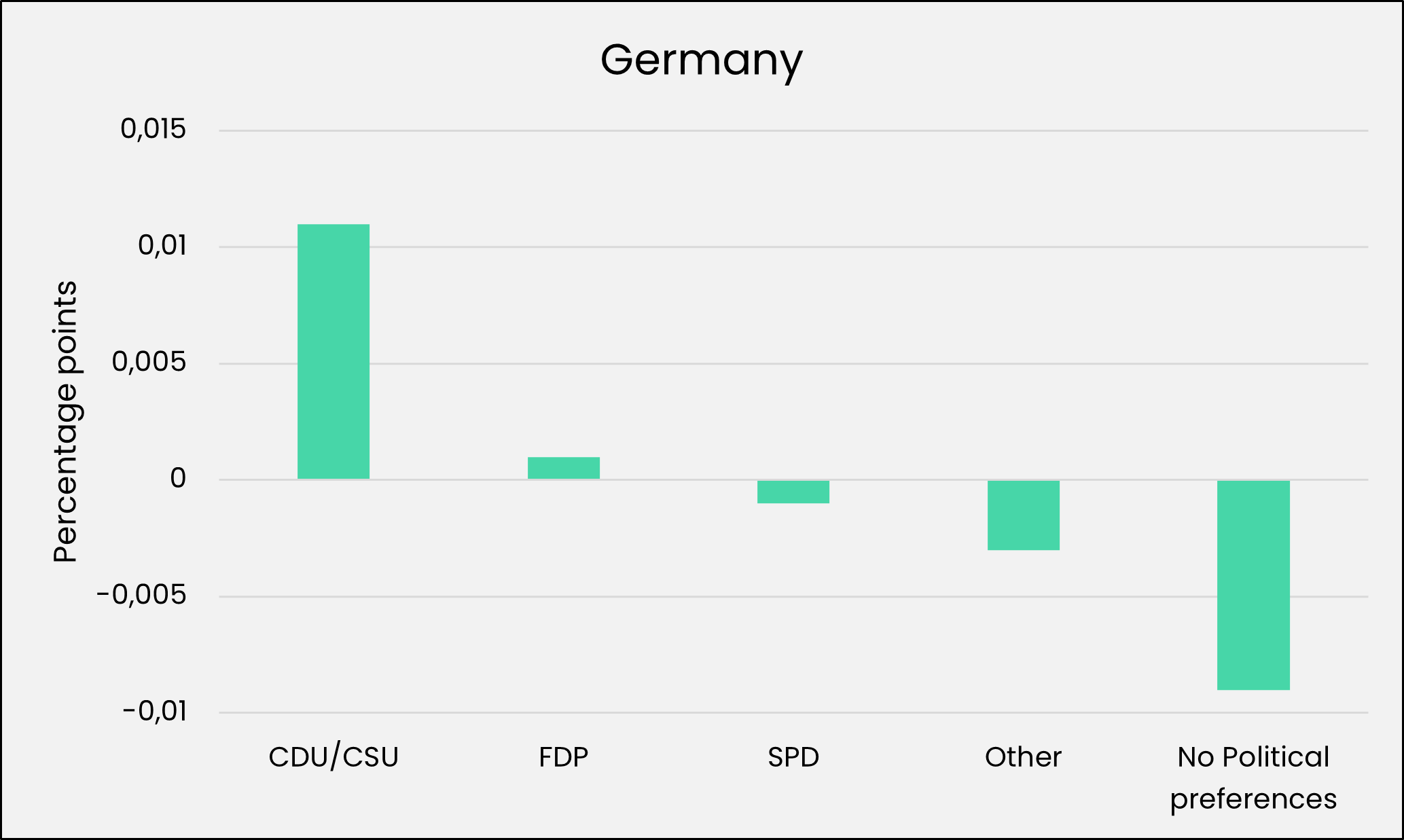

Multinomial logit regression analysis produces a clear pattern of results (see Figure 2 below):

- In the UK, economic insecurity is strongly associated with greater support for the Conservative Party, with no significant effect on support for Labour.

- In Germany, insecurity increases support for the CDU/CSU, with no effect on support for the SPD.

These effects persist even when controlling for income, employment status, and home ownership, suggesting that economic insecurity itself – and not just financial hardship – drives these movements. The measure of economic insecurity that we propose is also shown to be a better predictor of political preferences than other common indicators of insecurity that have appeared in the literature.

Figure 2. Economic insecurity and political preferences in the UK and in Germany

Note: These figures show the marginal effects of an increase of one standard-deviation in economic insecurity on different political preferences.

In addition, data from the Understanding America Study show that higher economic insecurity increased overall voter turnout and boosted support for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton, with no significant effect on third-party candidates.

If economic insecurity has contributed to Right-wing support in the UK, the US and Germany over the past three decades, could it also be linked to the recent surge in populism? Our findings suggest that it is. Considering the 2016 Brexit referendum, we find that a one standard-deviation increase in economic insecurity is associated with a one percentage-point rise in the probability of supporting “Leave the EU”.

One might expect that parties on the left of the political spectrum—emphasizing redistributive policies and a strong concern for the living conditions of the most vulnerable—would be the natural beneficiaries of economic insecurity. Yet our results point to a different dynamic, which can be better understood through insights from psychology. Economic insecurity tends to heighten the psychological need for security, a need that is strongly associated with greater adherence to conservative values. In this context, the (perceived) ability of right-wing parties to impose order and manage uncertainty may appear more reassuring, and thus attract greater support among those facing economic hardship.

Conclusion

Our results here are important. It is common to argue that insecurity reduces individual well-being; we here show that it also feeds through to political outcomes. Rather than encouraging a withdrawal from politics, economic insecurity seems to encourage political activism, but of a certain kind: support for the Right.

However, much remains to be discovered about economic insecurity. Its multidimensional nature, the mechanisms through which it influences behavior, and the best ways to measure and address it are still subjects of debate. Available data are often limited, the concepts remain vague, and the implications are far from fully understood. It is in this context that the Luxembourg National Research Fund has co-funded a Doctoral Training Unit (DTU) bringing together 14 PhD students and Professors of both the University of Luxembourg and LISER, to study in depth the measurement of economic insecurity, its causes, its consequences, and possible policy responses. This initiative, called EICCA (see https://eicca.uni.lu), aims to produce cutting-edge interdisciplinary research to better understand and address the phenomenon of economic insecurity.